BEWES: I want to ask one more question and then we’ll open it up. It relates to the Foucault quotation. Foucault says several things in this little interview. First of all, that there is no love in Maria Malibran, and this claim has to do with the distinction he makes between love and passion: “These women are chained in a state of suffering that binds them together which they are unable to break away from but which at the same time they would do anything to free themselves from. All of this is different from love. In love there is, in a way, someone who is in charge of this love, whereas passion circulates between the partners.” So Foucault is wanting to establish an absolute distinction between love and passion, at least as it is dealt with in the film. I wonder if this might be a sort of taking-off point for placing this film in the history of cinema, a history that has been so fascinated by passion and affect. Where do we place this film, for example, in relation to Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, with its prolonged shots that focus very closely on Joan’s face, that, in fact, encourage us really to enter into her passion? Where, on the other hand, is this film in relation to an art project like Bill Viola’s The Passions, where he slows down the movements of the actors to such a degree that, again, one is apparently encouraged to enter into the minute variations of an experience of passion. What is this more operatic, more performative engagement with emotion doing in relationship to that larger history?

KOCH: I think there are two notions of passion involved here. One is this Christian notion of passion as suffering; and then you have the idea of passion as a drive that can be enacted through the body, through the flesh, so to say. In Schroeter you definitely have these illusions with the miserere: it goes to these musical forms and also to sculpture and so to a wonder of sufferance that leads to healing. That’s the fairy tale. But I think there is something else involved here that has more to do with what Alex referred to in his statement: the time and timing of passions. There is a moment in the film where you have the repetition of the woman taking back her hair. She is doing this monologue about time: “Let’s postpone it for tomorrow. Let’s postpone it for tomorrow.” This is like a quote from the time-theories about melodrama, where passions have to be unfulfilled. So it’s always something that will be tomorrow, but tomorrow will never happen, because people will die before. They die not after tomorrow, but before tomorrow. This is a negative time construction in melodrama, and I think Schroeter refers here to these melodramatic, let’s say, prerunners of opera — and also the cinematic post-runners. So that this is, you know, a repetition that has absolutely no future. Not the Kierkegaardian or Deleuzean concept of repetition, nor what Cavell is doing in The Pursuit of Happiness. It’s really much more leading to a kind of stilled sense that is a kind of social death.

DÜTTMANN: Maybe that’s also — this is not something I normally do, but why not? Lynne [Joyrich] said to me, it’s an example of queer cinema. Maybe this is where the queerness might come in. Whereas the heterosexuals expect something to happen in half an hour, and reasonably so — and there will be a fulfillment, or not — the queerness of the film is, as it were, to inhabit those two images, that repetition, that constantly repeated gesture that leads nowhere, because it’s only that one moment of passion without a development, which is both the quintessence and the incapability of fulfillment — but maybe there’s nothing else. Maybe that’s what there is.

KOCH: That’s a Baudelairian moment. I mean, À une passante. I would say, the modernist paradigm.

SZENDY: I would just add something very quickly to these thoughts. So it seems to me that when Foucault talks about passion versus love, what he says is that passion leads nowhere. Whereas love, he says, expects something in return, and is supposed to lead somewhere. So there is something, we could say, non-economic or an-economic, like a pure expenditure, in passion. This is the reason he says that passion is communication — not communication in the sense of communicating something, but more like a contagion, something that has no direction.

DÜTTMANN: Communication without transparency.

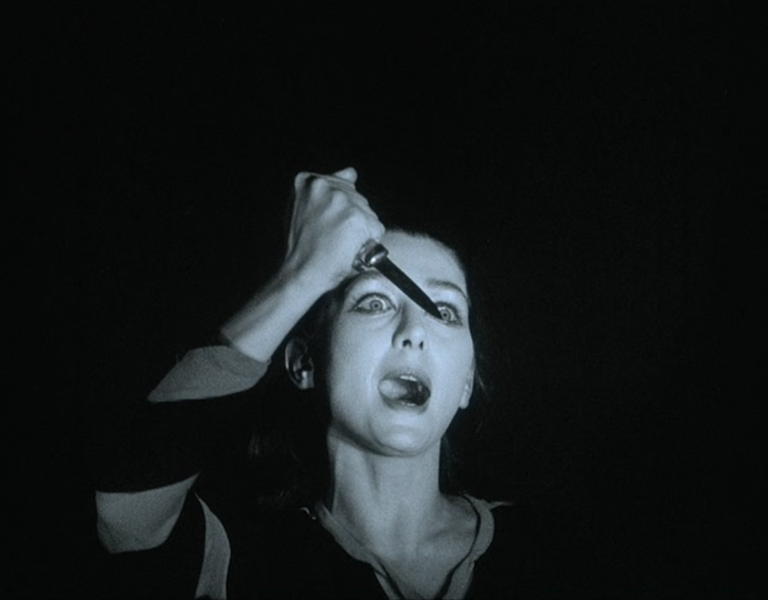

SZENDY: Yes. I was really interested in what Alex said: this quintessence of passion, this sort of quintessence of impossibility. So I was thinking of the eye and mouth and what happens. In a way, cutting or carving out the eye or graphically cutting out the mouth. It’s like isolating a pure eye or a pure mouth that is not meant to convey something. It’s just there, but at the same time, it’s an impossible eye or an impossible mouth. It’s not meant to sing something or see something. It’s just there.

DÜTTMANN: It’s like in Beckett’s Not I! So — this is when we open it up.

LYNNE JOYRICH: Thank you for programming this film, which was amazing, and for your comments. I totally agree with what everybody said, and I was thinking that it’s very much, as you were saying, Gertrud, about the construction of cinema itself, between repetition and also — as you were talking about, Alex — tableaux. So there is both repetition and a sort of stillness; both body and voice that are there but not necessarily synched; both sound and image, which may come together or never come together, because — as in melodrama — things never quite match up. So I wanted to make the point that it’s about not just the operatic but specifically the cinematic melodramatic. It’s so much in reference not just to silent cinema melodrama but also to ’30s, ’40s, ’50s melodrama (like the work of Douglas Sirk). It’s playing with the inherent melodramaticness, in a way, of cinema — and this ties to the queer issue, because this is such a strong through-line in queer cinema. There was so much about this that resonates with, for example, the work of Jack Smith or with Kenneth Anger, of course with Fassbinder, with Todd Haynes, and even, in some ways, with John Waters. Across the history of queer filmmaking there’s been this deployment of melodrama as a way to get at — what? — the unsmoothedness of affect, the “jarredness” that affect can be. So again, I’m wondering if any of you have more thoughts about the way this ties to the history of queer cinema or even just the deployment of gender and sexuality, the performativity around gender and sexuality.

BEWES: Well, we haven’t yet mentioned the performers, such as Candy Darling ...

SUZANNE STEWART-STEINBERG: Alex, when you were talking about the repetition compulsion that leads, in your opinion, to a kind of “abstraction” or “idealization” — these are the terms — but then you say, to “opera.” So, If I’m understanding correctly, you’re not saying it’s the abstraction that is the essence of opera, but that opera is that kind of abstraction. Is that correct? OK.

And to combine that with what, Gertrud, you were saying about the merging of foreground and background into the making of a sound-image. So I’m wondering how these two work together — the making of a sound-image, and opera as abstraction/idealization? One way, maybe, of thinking about this is to ask how we even talk about the music here. Because it’s not just sound bites. These are very, very carefully chosen pieces of music.

DÜTTMANN: “Curated,” they would say today.

STEWART-STEINBERG: Curated! Yes. Some are completely, of course, out of her time. Puccini, for example, does not belong there ...

BEWES: Nor Bessie Smith ...

STEWART-STEINBERG: Why you have Beethoven’s Triple Concerto going on for a long time is very peculiar. So it’s not demonstrative of anything, but, nevertheless, there is a choice. So I’m wondering how these two moves that you describe — opera and its cinematic form of existence — how we actually think about that in terms of the music.

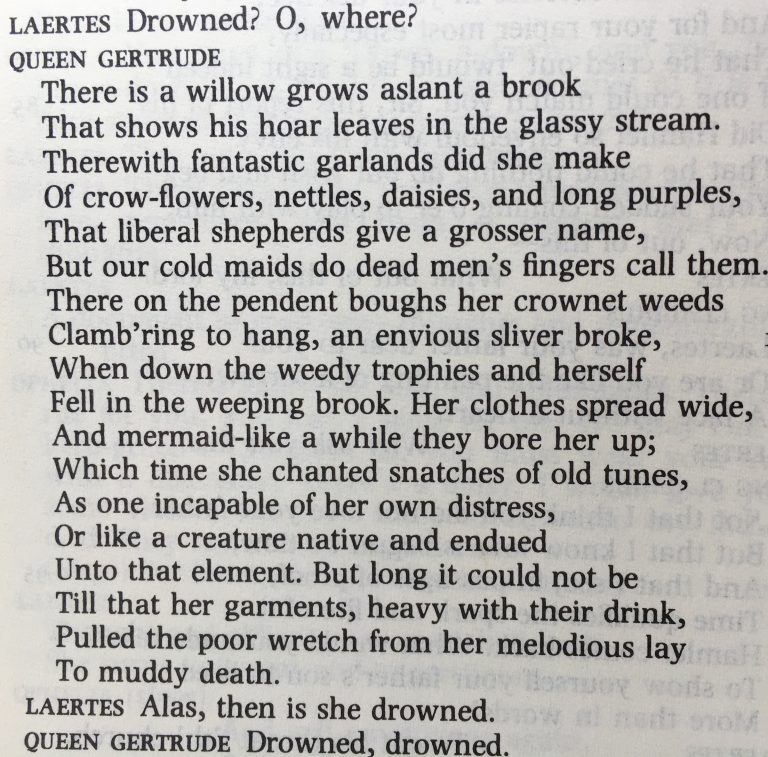

SZENDY: I don’t really have an answer, just a thought. Maybe Alex will have some more. There is a line — I think it’s a quotation from Hamlet, about Ophelia, and it says something about “snatches of old tunes.” That, in a way, is the structure of the whole film. I think — and I don’t know if you would agree, Alex — I think it has something to do with what you were trying to say about the quintessence, because all these snatches of tunes, they try to catch, to seize, to grasp the quintessence of something — maybe passion, an affect, I don’t know. They do that all the more since they are snatches, precisely.

It has also something to do with the knife, cutting, editing, but the quintessence.

KOCH: I think what was really new — but it was shared by this whole group of directors at the time, when you think about the Fassbinder films — these kinds of schmaltzy melodramatic songs play an enormous role, so what I think was the interesting work Schroeter is doing is not only the editing, but that it goes into a flow. This I always found very amazing. It’s like a composition. So, it’s composed and it has these variations between these popular songs and opera arias and absolute music.

STEWART-STEINBERG: Absolute music?

KOCH: Yes.

STEWART-STEINBERG: Is it Stravinsky at some point?

KOCH: Yes. Everything is there. It’s going into flow. This was my idea: to say, on some level, you don’t have any more sources. It is indeed a liberation from film music, from any inner diegetic need. It comes as a kind of composition in itself, and this I find very intriguing, in, let’s say, this combination of gestures. What film shares with theatre, but not with painting and other image-based arts, is that it works with live action, live actors. This, I guess, is a relationship between singing and doing, performing music, which are both bodily activities. It’s beyond electronic music at the time. You have these very old discs that are playing, historic things. Callas, all the campy things. It goes back to this problem of voice recording, sound recording, music that was before the image as in the orchestra for silent films. Then, how to bring the sound into the image? This was the main aesthetic problem for sound film. You can do it naturalistically, which is boring, as we know, but here, I think, you have two autonomous movements that are both referring to the fragility of the embodiment of sound in human bodies.

STEWART-STEINBERG: Isn’t there a strange way in which the music is diegetic?

KOCH: No. I think it’s diegetic only insofar as we have kind of micro-narrations of passion in it, but it’s not diegetic in the sense of a classical melodrama where you would have leitmotifs for the young hero, and so on. So no. It’s not Wagnerian.

BEWES: Until the end, right? Until her death, because at that moment ...

JOYRICH: Well, there are some moments even before that. But it does seem like the notion of syncing runs across the whole film. How to sync bodies with one another? How to sync bodies with affect? How to sync sound with image, or not? Again, that to me is the queerness of it, because there is no natural syncing, and it seems that the film plays with that. There’s also an affect of humor. There are moments that, because of the extreme passion, are really hilarious. The film is very funny in many ways. So there’s also the syncing, or lack of syncing, between the tragic and the comic.

DÜTTMANN: Yes, because that’s part of the repetition, once again, which is not being domesticated or submitted or integrated into an order, but is just the repetition itself. I wanted to stress something that Peter just said, one more time, because I also have the strong feeling that we don’t simply listen to that music, which so strangely fits, when actually it shouldn’t fit because it’s radically heterogeneous. Suddenly you hear this very slow interpretation of Ramona, and then, in the beginning, it’s Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody, so you know, it’s like things that don’t normally go together; but here we buy it. I do at least. It’s really mysterious why that happens. That mystery remains to be solved, perhaps, but there’s also the fact — and this is what Peter just said — that we listen to this music as if we were listening to an echo or snatches of old tunes. We don’t listen to it as something which is simply there. So there again you have this moment of repetition, something which is brought back. If cinema is also about a second vision, then everything you hear, the music, you have to listen to as if it were snatches of old tunes and not something simply, immediately, present and given.