“Another Handsome Dwelling”: American Renaissance at 13 Brown Street

Andrews House, known for eight decades as Brown University’s Health Services, received only a passing mention in a 2006 campus heritage report, but the four-storey mansion, originally home to the textile magnate Alfred M. Coats and then to Governor R. Livingston Beeckman, was an intimate part of the economic, social, and political fabric of Rhode Island in the first decades of the 20th century.

Alfred M. Coats, Heir of the Local “Cotton Thread King”

Andrews House has its origins in the New England textile industry. The house’s first owner was Alfred M. Coats (1863–1951), a member of a prominent Scottish family in thread manufacturing. J. & P. Coats, historically among the first British multinational companies, assumed control over thread manufacturing facilities in Pawtucket in 1869, shortly after the abolition of slavery. The plant was among Pawtucket’s largest employers, expanding from 550 to 2,500 employees between 1870 and 1910, and its site was registered as a historic district in 1983 (National Register of Historic Places Inventory).

Thread and textile production had long been central to Rhode Island’s economy, which, as Brown’s 2006 Slavery and Justice Report underscores, created deep ties among the Southern plantation economy, Rhode Island’s industrial growth, and the private wealth that endowed and built the University. The formal end of slavery in the United States yielded neither the land property transfers nor the increased worker mobility that might have supported economic and political emancipation. Instead, as historian Sven Beckert recounts, new labor regimes in the postbellum period founded on racial inequality allowed “a rapid, vast, and permanent increase in the production of cotton for world markets,” with U.S. cotton production doubling between 1861 and 1891 (Beckert, 291–292).

Alfred M. Coats, who lived most of his life in Providence, took on an executive role at the J. & P. Coats plant in 1896 and was general manager from 1902 to 1910. Coats was a lifelong business partner of the Rhode Island textile magnate Frank Sayles, whose gift enabled the construction of the second building at Brown’s Women’s College, a gymnasium that bore his name until its conversion into Smith-Buonanno Hall in 2001. Coats and Sayles cofounded the Punch River Textile Company and the French River Textile Company and shared interests in local banking, manufacturing, and energy companies.

In his 30s, Alfred Coats, having assumed new responsibilities in the family business and recently wed, commissioned the design of two Rhode Island homes, both after English historical styles, from the trendsetter architect Odgen Codman, Jr. The first of these, known as Landfall, was a Newport summer residence completed in 1896–1897. The second, a winter residence combining two parcels at the junction of Brown and Charlesfield Street, entailed the demolition of another landmark house, an “old-fashioned brick homestead [...] occupied by the heirs of Deacon Read, at one time so well known in the woolen trade” (Providence Journal, Apr. 14, 1900).

At an estimated $125,000 in construction costs, the house and its stables were the most expensive project reported in a Providence Journal review of structures built in 1900: It exceeded the combined cost of 15 other houses erected in Ward 1, the cost of a new church in Ward 6, or a manufacturing site in Ward 4 — and it dwarfed the $30,000 price tag of the new home built by Brown’s president William Faunce in Ward 2 (Providence Journal, Jan. 2, 1901).

Ogden Codman, Jr. and the Standards of Architectural Taste

Born the same year as Alfred M. Coats, Ogden Codman, Jr. was — as the book he cosigned with his Newport patron, the writer Edith Wharton, indicates — an architect on a mission. The Decoration of Houses, first published in 1897, denounced Victorian decorative eclecticism, foregrounding instead the interdependence of functionality, structure, and ornament. The book was Edith Wharton’s first major publication.

At the same time that it claims a general applicability to houses of all sorts, The Decoration of Houses professes its faith in oligarchical transformations of taste. “Changes in manners and customs,” Wharton and Codman wrote, “no matter under what form of government, usually originate with the wealthy or aristocratic minority, and are then transmitted to the other classes” (Wharton and Codman, 7). Active in Boston, New York, and Newport, Codman catered to the East Coast elite, putting into practice a project of trickle-down aesthetics.

In broad terms, The Decoration of Houses offers one template for the “American Renaissance” in architecture. Structural and decorative features of modern homes should, according to the book, be composed after a portfolio of historical styles in Italy, France, and England from the 15th to the 18th centuries — styles that themselves turned to “the Roman idea of civic life” to accommodate the “spectacular existence” of the nobility. Modern houses were to accommodate the necessities of both general entertainment and family life; however, the work of the architect was to go beyond generalities to integrate “the individual tastes and habits of the people who occupy it” (Wharton and Codman, 19).

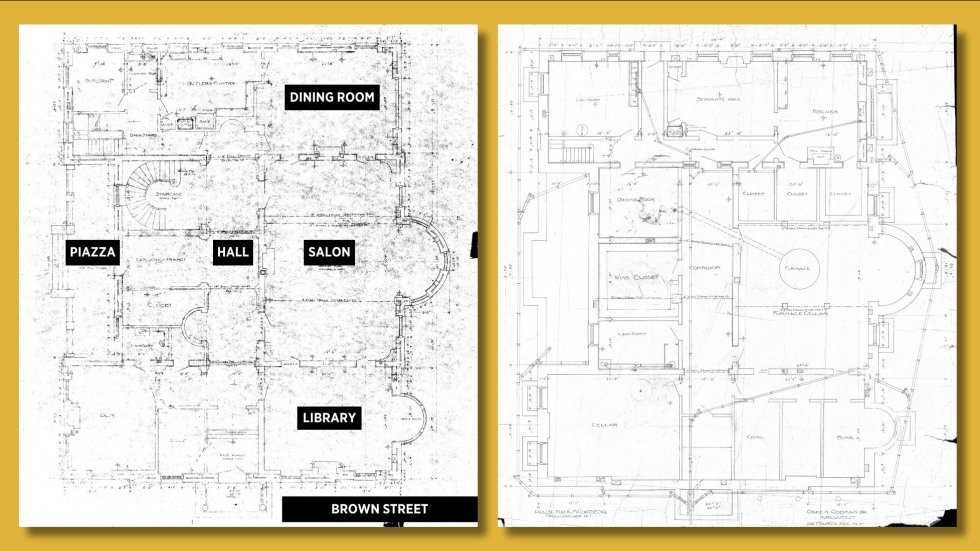

Ogden Codman's architectural plans designated the first floor as a space for hosting. Guests entering from Brown Street would pass through the marble vestibule and hall to access the library, salon, and dining room. A secondary hall of mirrors opened onto the exterior piazza and the garden. The first floor also provided service and coat rooms that complimented the kitchen, wine closet, servants' mall, furnace cellar, laundry, and drying room in the cellar.

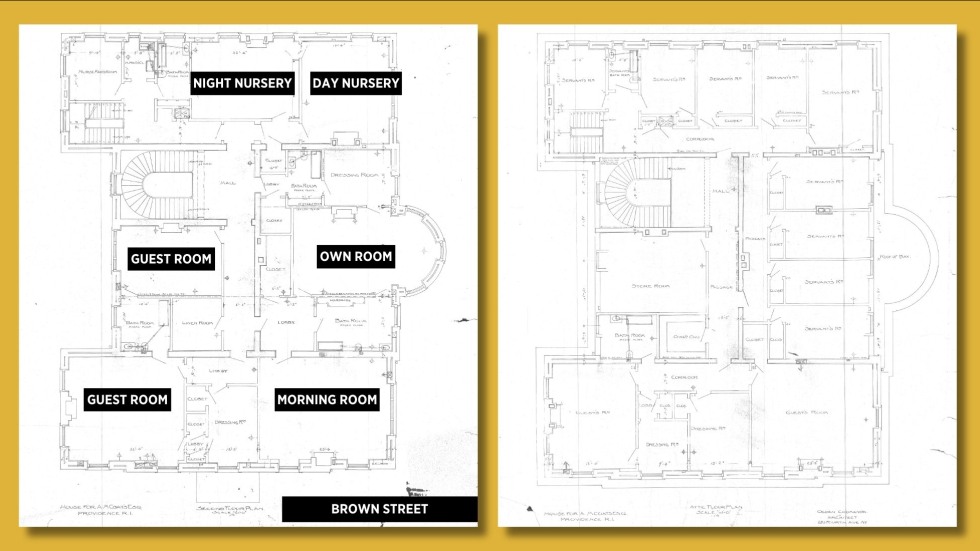

Codman assigned the second floor to domestic life: at the center, a main suite with adjacent bedroom, dressing room, and bathroom; on the west side (by Brown Street), a morning room; and on the east side, the children's nurseries and a room for their governess or nursing maid. Guests could stay on the second or third floor. The largest portion of this "attic" floor plan was assigned to the servant's quarters divided into nine rooms.

The house at 13 Brown Street followed the architectural injunctions of Wharton and Codman to the letter, which encompassed careful attention to walls, doors, windows, fireplaces, entrances, and stairs before turning to various categories of rooms. Architectural maps for the building delineate clear distinctions between a first floor dedicated to social life, a second floor focused on domestic life, and a third floor offering additional quarters for guests and rooms for servants. The basement was reserved for logistical support, from coal storage and furnace to the laundry rooms, kitchen, and wine closet.

The “effectual barrier” of the front door off Brown Street opened into a weather-proof marble vestibule and hall, “passageways” designed to make a forceful “first impression” as guests accessed the salon, the library, the dining room, and a lounge or “den” (a term Wharton only used with scare quotes). From the side hall paneled with mirrors, large double doors led to “a porch of white marble” that overlooked an enclosed yard (Providence Journal, July 9, 1902). The Providence society pages document various teas, parties, dance dinners, and musical events by amateurs and professional artists that could double as fundraisers for charities, particularly to support causes related to women and public health.

Alfred M. Coats’ wife Elizabeth Barnewall Coats welcomed into her home artists like the social portraitist Lydia Field Emmet and the mezzo-soprano Susan Metcalfe. The Coats commissioned two paintings from Emmet in 1904 and 1906, including one of their daughter Mabel. Emmet writes with affection of the “nice normal peaceful happy little party” formed by the Coatses and their three children along with their “good natured gentle” Irish governess “desperately interested in American history” (Letters, c. 1904). Emmet’s portrait of Mrs. Coats is now in the collections of the RISD museum.

The Rhode Island Governor’s Home

Having mediated between cotton plant workers in Pawtucket and the J. & P. Coats board of directors in Scotland for a decade, Alfred Coats resigned from direct management in 1910. By 1913, the Coats family had left their Brown Street mansion for another residence in Providence and leased the building to Robert Livingston Beeckman (1866–1935) and his wife Eleanor Thomas Beeckman.

Born in New York City and educated in Newport, Beeckman made his fortune on the New York Stock Exchange and earned notoriety as a polo and tennis player. He then became involved in Rhode Island politics, was elected to the House of Representatives as a member of the Republican party in 1908, and served in the state legislature before being elected governor in 1914 (Bicknell, 12). He was reelected governor for two more terms, in 1916 and 1918.

Given that Rhode Island does not maintain a full-time official residence for its governors, 13 Brown Street served as the executive mansion from 1915 to 1921. Beeckman inaugurated annual receptions and dinners for the state legislature, the members of the executive staff, the state supreme court justices, and the press. He also hosted — sometimes in partnership with Brown University — national figures of the Republican Party and guests that spoke to the role of the United States in WWI. These included former U.S. ambassador to France Myron T. Herrick; former U.S. President William Howard Taft; Republican party presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes (class of 1881); senator Henry Cabot Lodge, chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations; the Archbishop of York William Cosmo Gordon Lang; and General John J. Pershing.

The Beeckmans’ wealth allowed them to host in lavish style. The first floor walls would most likely have featured their personal collection of French and Flemish tapestries and embroidered armorial tapestries from the 16th and 18th centuries, which were briefly exhibited at the RISD Waterman Gallery in 1921. The late managing editor of the Providence Journal and Evening Bulletin, David Patten, in recollections published at the end of his career, mocked the luxurious clothing of the “lord of the manor,” his engraved silverware, and an “infest[ation]” of butlers, maids, and valets complemented by professional musicians performing from behind palm trees (Patten, 1954).

Following the death of his first wife and the approaching end of his time as governor, Beeckman announced his departure from 13 Brown Street. President Faunce and the Brown University Corporation immediately moved to acquire the property from Alfred M. Coats, securing at “a nominal cost” the first site of its new Faculty Club (Bulletin of Brown University, 1926, 24–25).

Image Credits

- J. & P. Coats Ltd. Thread Mills, Pawtucket, RI. Postcard, E. L. Freeman Co. no 10388 (made in Germany), no date (1-cent stamp rate). Cogut Institute for the Humanities, Brown University.

- 1899 Map of Providence, Rhode Island. Boston, Geo. H. Walker & Co. Harvard Map Collection G3774.P9.1899.G4.

- Portrait of Mrs. Alfred M. Coats (Elizabeth Barnewall Coats) by Lydia Field Emmet (1866–1952). Oil on canvas, 153.7 x 103.5 cm (60 1/2 x 40 3/4 inches). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Douglas Campbell, Jr. 1995.089. RISD Museum, Providence, RI.

- "House of Mr. Alfred M. Coats, Esq." Architectural plans by Ogden Codman, Jr., Architect, 281 Fourth Avenue, New York City. Brown University Facilities Digital Records.

- Letter from R. Livingston Beeckman to William H. P. Faunce, January 11, 1916. Brown University John Hay Library, MS-1C-9, Box 14, Folder IV.65. The Providence Journal reported on the dinner in its Sunday issue and published the full guest list ("Dinner Parties of the Week," January 16, 1916, fourth section [p. 32]).

- In the background: Photograph of the Brown Street facade of the Alfred M. Coats mansion, taken by local resident Harold Mason (1881–1944), most likely in the 1910s or 1920s. Courtesy of the Providence Public Library Digital Collections.

Primary Sources (Selected)

- “A Few Social Affairs,” The Providence Sunday Journal. February 6, 1916, p. 35.

- “Another Handsome Dwelling: It Will Be the Winter Home of Alfred Coats on Brown Street.” The Providence Daily Journal. April 14, 1900, p. 12.

- “A Prosperous Year. The Building trades Did a Fair Amount of Business in 1900.” The Providence Daily Journal. January 2, 1901, p. 9.

- “Beeckman Collection of Rare Tapestries on Exhibition at School of Design.” The Providence Sunday Journal, February 6, 1921, p. 58.

- “British Archbishop [of York William Cosmo Gordon] Decries Peace Talk.” The Providence Daily Journal, March 9, 1918, p. 4.

- “Dog as Burglar Alarm: [...] Bull Terrier Awoke Caretakers of East Side House [...] Residence They Attempted to Enter Occupied by Alfred M. Coats.” The Providence Daily Journal. July 9, 1902, p. 12

- “Governor Presents His Collection of Hangings to R.I. School of Design.” The Providence Journal, December 29, 1920, p. 1.

- “Guests in Town.” The Providence Sunday Journal, June 2, 1918, p. 34 [on Henry Cabot Lodge at Brown University and at 13 Brown Street].

- “Hugues Now Ready to Begin Campaign.” The Providence Daily Journal. June 22, 1916, p. 7 [Charles Evans Hughes at Brown University and at 13 Brown Street].

- “Local Society.” The Providence Sunday Journal. March 4, 1906, p. 11 [on Susan Metcalfe].

- “Local Society.” The Providence Daily Journal. January 27, 1907, p. 22 [on Susan Metcalfe].

- “Myron T. Herrick at Textile Club.” The Providence Sunday Journal. December 12, 1915, p. 4 [introductory speech by Beeckman and hosting at 13 Brown Street].

- “State and City Join in Paying Tribute to Gen. John J. Pershing.” The Providence Sunday Journal, April 18, 1920, p. 1.

- Account Book of Lydia Field Emmet. Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Emmet family papers, series 5 (Business Records), box 8, folder 10 [The Coats portraits are listed in 1904 for $1,150 and 1906 for $1,000].

- Bulletin of Brown University: Report of the President to the Corporation. Providence: Brown University. Vol. XXIII, no. 6 (November, 1926).

- Letters from Lydia Field Emmet to W. M. Emmet, c. 1904. Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Emmet family papers, series 2 (Correspondence), box 2, folder 43.

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams. “Hon. Robert Livingston Beeckman.” In The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. New York: The American Historical Society, 1920. volume 4, p. 11–12.

- Patten, David. "Tillinghast Set Political Course for Beeckman." The Providence Journal, January 14, 1954, p. 5.

- Patten, David. “The Beeckman Era Proves Lesson in High Living,” The Providence Journal, March 22, 1954, p. 12.

- Wharton, Edith, and Ogden Codman, Jr. The Decoration of Houses [1897]. New York and London: W. W. Norton, 1997, revised and expanded Classical America edition.

Secondary Sources

- Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Vintage Books, 2014 (especially pp. 274–292).

- Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice and Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. Brown University’s Slavery and Justice Report with Commentary on Context and Impact. Providence: Brown University, 2021. (especially pp. 155–158).

- Metcalf, Pauline C. (ed.). Ogden Codman and the Decoration of Houses. Boston: The Boston Athenaeum, 1988.

- R. M. Kliment & Frances Halsband Architects, Campus Heritage at Brown University: Preservation Priorities, February 2006.

- Widmer, Ted. Brown: The History of an Idea. Providence: Brown University, 2015 [on the presidential campaign and political career of Charles Evans Hughes, see pp. 152–155].

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by a Brown University Spring 2024 Undergraduate Teaching and Research Award. Thanks are due to the staff of the John Hay Library and RISD museum, particularly Jennifer Betts, Ray Butti, Douglas Doe, Sionan Guenther, Maureen C. O’Brien, and Jasmine Sykes-Kunk. We owe to project manager Shirley Mak (Facilities) and architect Kristen Caulk (Goody Clancy) access to the digitized records of architectural maps and contracts. We also gratefully acknowledge guidance from Seth Rockman, Associate Professor of History, and Gregory Kimbrell, Communications Manager of the Cogut Institute.